I know that SPs are a variety of snuffs usually flavored with bergamot and sometimes other things on the side. Most of my favorites, from Grand Cairo with it hints of spices and Gold Label with its leathery tobacco flavor to Tom Buck with its slight pepper tone are SPs. But I still don’t know what it stands for or what exactly makes a snuff an SP. And what the hell does SP stand for? Snuff Powder? Scented/perfumed? Super Prime? Sexy Pimpin’? Does anyone know?

Nobody is certain. Some believe it’s short for Spanish (a googling of “Vigo snuff” will explain this), others say that it’s Sheffield Pride. I’m glad that you brought this up though, because I remembered just this morning a thread where–I think it was Snuffster or PhillipS–mentioned that SM stood for Sheffield (or was it Sharrow?) Medicated. It occurred to me, and I’ve been meaning to bring it up, that maybe then SP could mean Sheffield Plain. Plain, as opposed to medicated if you follow me.

You know there will be no definite answer which is for sure. But for me these explanation from snuffbox.org.uk is the really good: “Nobody knows what S.P. stands for. It has been thought to be “Sheffield Pride” because of its main purveyors, Wilsons of Sheffield. But now the consensus is that it means “Spanish” : perhaps because of the Havana snuff looted from a Spanish convoy (though then referred to as “Vigo” snuff) - by Admiral Rooke in 1702 and paid to his sailors as prize money - in consequence of which snuff became cheap and hence popular in England, no longer the reserve of the toffs (or “toffee-nosed”). (The first snuff factory was set up in Seville in the C16th: the grated tobacco produced in that Royal tobacco factory was known as “Spaniol”.)” Anyway: I like them ;-)) and that’s the main thing for me.

I fall in the “Spanish Prize” camp. From what I’ve read it has the most backing from the erudite.

@Screwtape - I have never said it was sheffield medicated and I very much doubt Philips has either. I have always gone with SP as meaning, simply, ‘Spanish’. You are probably remembering us talking about the possibility of it meaning ‘Sheffield Pride’. Medicated snuff didn’t exist when this abbreviation came into common use. I go with the simplest theory - Spanish, and that ‘SP’ was orginally written ‘Sp’ and used as a stock book abbreviation to refer to Spanish type snuff - this may have originally been the captured Spanish snuff that Rooke partly paid his sailors with, although there is no proof either way. It may have originally meant several types of Spanish snuff and the abbreviation was nothing more than a shorthand used in the business. ‘Spanish Prize’ is equally possible, it has to be said. I think the ‘Sheffield Pride’ idea is a much later invention, probably originating from the little booklets that were occasionally published by the snuff trade in the last century. McCausland, who in the 1950s had accesss to the FandT archives, the Bridgman-Evans family documents and the Wilsons family of the day, makes no mention of it.

Grand conundrums such Fermat’s Last Theorem are trifles as light as air compared with The S.P Question - a puzzle that great minds have wrestled with for many a weary year. A novel theory based on Wilson’s old lettering system (S.X) is found at - http://snuffhouse.org/discussion/2612/what-is-sp/p1 - but flounders because if S is for Sharrow then what does P stand for? Even the weariest river winds somewhere safe to sea, but unless one is satisfied with the (Sp)anish appellation the ‘Question’ remains unanswered, its dark tributaries meandering forever outside the frontiers of human knowledge. :< )

Oops, I see that someone came up with my Sheffield/Sharrow Plain theory there. But that was the thread I was thinking of. Thanks PhilipS. @Snuffster - miscommunication there. I was saying that you had said that SM was Sheffield/Sharrow Medicated. (I couldn’t remember if it was Sheffield or Sharrow.)

Yes, me not reading your post properly:)

This SP mystery has been troubling my mind no end,but i failed to bring it up fearing to sound ignorant.!

Quoting here: ‘Speculating here, but Richt could refer to a person. At one time it was quite frequent for valued patrons to request tailor-made snuffs that were named after them or their fancy. We’ve seen it with Hardhams. Dr. James Robertson-Justice etc. Here we probably have a snuff created for a certain Mr (or Mrs) Richt, who have long since shuffled off their mortal coil, leaving the snuff as their sole epitaph.’ Therefore I consider ‘Samuels’ or ‘Somebody’s Plain’, or Perhaps ‘Sam Philips’s’ sort a possibility that cannot be quite ignored,

‘Up to snuff’ is a phrase that might be explained by somebody…

All I know if I love the scent of an SP. Apathy kicks in after that and I just stop pursuing anything more…

Wow. I’m glad to have started such an interesting discussion. Thanks to all who commented.

SP 100 is one that I’ve recently had a go at. Most people who do, like it…My favourite WS SP. Don’t ask me why though. I’m on my second large tin and still keep reaching for it. Very easy going.

SP100 and Toque SP Extra are my favourite SP’s, both lovely in their own way. Stefan

Its SP Extra and Best SP for me but I have yet to try SP100, I’ll have to get me a tin on my next order.

I agree Stefan, though McCrystles SP went quick when I bought a tin.

up to snuff means the tobacco is off high enough quality for snuff.

Bob that sounds reasonable. ‘Cutting the mustard’?. Vinegar, sharp, astringent?

Up to snuff Meaning Initially, the phrase meant ‘sharp and in the know’; more recently, ‘up to the required standard’. Origin ‘Up to snuff’ originated in the early 19th century. In 1811, the English playwright John Poole wrote Hamlet Travestie, a parody of Shakespeare, in the style of Doctor Johnson and George Steevens, which included the expression. “He knows well enough The game we’re after: Zooks, he’s up to snuff.” & “He is up to snuff, i.e. he is the knowing one.” A slightly later citation of the phrase, in Grose’s Dictionary, 1823, lists it as ‘up to snuff and a pinch above it’, and defines the term as ‘flash’. This clearly shows the derivation to be from ‘snuff’, the powdered tobacco that had become fashionable to inhale in the late 17th century. The phrase derives from the stimulating effect of taking snuff. The association of the phrase with sharpness of mind was enhanced by the fashionability and high cost of snuff and by the elaborate decorative boxes that it was kept in.

Tobacco is a North American plant, there was absolutely no tobacco of any kind anywhere in Europe before the discovery of North America. What ever the Romans may have snuffed it sure wasn’t tobacco.

I do believe he has a good point Vathek!

Regardless of the historical derivation, I propose we adopt “Satisfactorily Piquant” as the official Snuffhouse meaning of the SP designation, on the grounds that it is the only meaning that actually provides a description of the group of snuffs in question.

PipenSnusnSnuff - A noble proposal! Although I kind of stick to the Spanish tale. This is quite an old Urban legend conundrum concerning snuff. I do like the fact that it is quite descriptive. SP snuffs are a joy, and the ability to try so many variants is truly amazing. I for one have tried so many, but just this week was able to try the SP No1High Mill from Kendal, and was once again delighted with something familiar yet unique. Viva la Difference!

I’m pretty sure that it was 2 random letters placed together for the express purpose of starting Saturday night pub fights over their secret meaning… :^)

WTF is going on here. Juxtaposer talking sense and Vathek making things up? Have I stepped into Bizzaro Universe Snuffhouse?

Funny shit eh?

First I’ve ever heard about Romans taking ‘snuff’, - as noted, can’t have been tobacco. where are the citations for that? (‘Paulatim’ suggests in small amounts to me rather than slowly, though I’ve little Latin and less Greek. Pulling our legs?). I’ll go with ‘Splendid Pinch’, since apparently it’s anyones guess.

I like the first explination I ever heard. Which was that no one knows what it stands for, because it did not stand for anything. It essentialy a ledger code or nothing more or less then a product code or a shipping code. Sort of like 1Q by lane, which was called I.Q. at my local. I still think that is the most likely explination. It doesn’t feed the mystery like other theories but it does explain why no one can find a solid meaning of S.P.

Lots of great tales being told here. The explaination that I have heard most often was that SP stood for either “Spanish” or “Spain” and was branded/seared/burned onto wooden cargo barrels in the days of sailing ships to signify their destination. Whether or not that is the real story is anybody’s guess.

Actually, the Romans were very heavy cigarette smokers. Julius Caesar got through 4 packs of Marlboro red in one senate meeting once. Cicero quotes him as saying ‘I love a tab, me’.

… intra bonun et in hoc bene Superbus Primam bonum quod dicit snuff estis…’ Tacitus, Ad Baccium. Woof Woof.

Snuffster that is a common misconception. His brand was larame ultras and romans were more into chewing tobacco, can’t expect anything else from the culture that invented the mullet.

Roman Centurions were notorious for their massive consumption of Macanudo’s. I’m sure I read that in Tacitus’ The Annals.

no, no, you guys got it all wrong, the Romans couldn’t get enough of that fine Cuban Habana.

yeah shows what you know! Romans called cigarettes pipes!

Well at least they had the sense to make wine in lead vats!

@howdydave is that like people are talking hear. Ship High In Transit.

Nihil carborundum illegitimati!

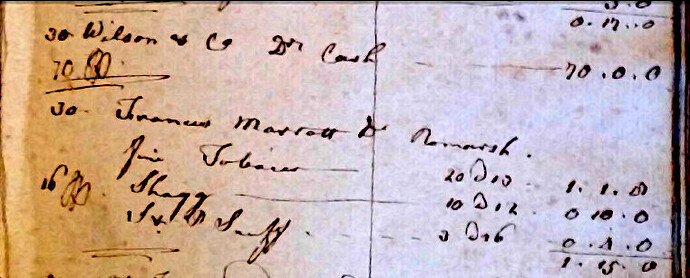

Wilson’s own site quote the Vigo battle as the source of SP. This has been accepted and passed on as truth without question. Snuffmen, like pre-Reformation ecclesiastical orders , speak as ones with authority, they sayeth and you believeth. “The booty from the captured Spanish galleons included a large quantity of snuff which was subsequently sold in London. Referred to as “Spanish” by the clerks, they soon abbreviated this to “SP”, thus originating the name of the most popular blend of all.” http://sharrowmills-online.com/company/snuffs.html This might be so, but what and where are the original sources to confirm this? All early sources I’ve seen to date state that the 1702 booty was sold in England as “Vigo Snuff” at three or four pence a pound, and described as “gross snuff from the Havannah“. The book ‘Social life in the reign of Queen Anne: Taken From Original Sources’ by John Ashton, for example, details the Vigo operation and its commercial aftermath but makes no reference to either ‘Spanish’ snuff or the alleged abbreviation (pages 158-159). The only references to S.P in contemporary clerical documents allude to the mundane S.P ledger (sales and purchases.) Likewise, the exhaustive book ‘Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1550-1820’ lists 4,000 products including many snuffs, but not S.P. Neither is S.P mentioned in Hassall’s magnum opus of 1854 or the surviving accounts of Fribourg & Treyer prior to 1920. The Vigo story might be true, but can anyone actually provide a reference to S.P snuff prior to the 20th century - let alone 1702! Would be very interested to read it.

“Although the above explanations of SP have the merit of ingenuity, the letters in fact derive from Latin, and stand for “sed paulatim” …” A scholarly explanation to be sure although Senatus Populus is more likely, indicative that the snuff was also popular with government and people outside Rome (sans QR).

‘Richt’ is ‘Right’, ie the right kind. Personal blends were invariably known as ‘sorts’, coming back to the comment made by petersuki.

After a great deal of research I think I’ve stumbled upon definitive proof that ‘SP’ equals Spanish Prize. I have found in “The Statutes at Large: From the Twentieth Year of the Reign of King George the Third to the Twenty-fifth Year of the Reign of King George the Third , inclusive. MDCCLXXXVI (1776).” That King George in regulating the import of snuff called it “Spanish Prize” and I quote. “Cap. XXI ……and regulating the importation of foreign snuff into this Kingdom; and for preventing the importation and running of foreign Spirituos Liquors, Tea and other prohibited goods, into this kingdom, in veffels (vessels) fitted out and armed as Privateers (Pirates). Whereas by an act of Parliament, made in the twentieth Year of the Reign of his prefent (present) Majefty (Majesty), intituled, An Act for extending the Provifions (Provisions) of two acts, made in the eighteenth Year of his prefent (present) Majefty’s (Majesty’s) Reign, and in the seffion (Session) of Parliament, with refpect (respect) to bringing Prize Goods into this Kingdom, to Spanish Prize Goods; and for repealing so much of the ast-mentioned Act as relates to the Certificates for Prize Tea and East India goods exported from this Kingdom to Ireland” In short all goods seized by ‘Privateers’ were to be hence fourth referred to as “Spanish Prize” Goods. Spanish snuff was called “Spanish Prize” and all other goods were to be known as “Prize Goods”.

I got a Spanish prize once. It took 4 weeks of ointment to make it go away. =(

@theratroom - Probably more like f.o.b.: Spain. f.o.b. = free on board or “free shipping as far as.”

@howdydave I may be a little slow but I don’t get the joke.

No joke… If you ever took any accounting or are in shipping you would know all about who pays for shipping. “FOB” is standard terminology in the USA. The International TLAs (3 letter acronyms) are: FCA, CPT and DDU. Well… the joke is that I’m the only one here being perfectly serious! (Just another example of my dry humor.)

@howdydave It did make me giggle that someone was looking for a punchline in your explanation. I have a degree in accounting and you’re dead on. FOB is about the only term ever used here in the US. In fact, if you watch the original Steamboat Willie cartoon (on YouTube I’m sure) the cow that they load on the boat has an F.O.B. tag on. Ahh…the small things I find joy in…

@Dogwalla – Who says that accountants don’t have a sense of humor? They just don’t appreciate all of our dedits and cribits!

@howdydave I have WAY too much personality to be an accountant. That’s why I’m in Marketing now I remember when I overheard two accountants laughing about a new hire they had. He had apparently credited an account instead of setting up an contra-asset, and they thought that was the funniest thing on the planet. It was like a redneck watching Jeff Foxworthy. None for me thanks.

Me too… It was just numbers (too dry,) so I went into software systems instead. Since there was absolutely NO software documentation, I ended up as a technical writer. Hence all of my plays on words, most of which go unappreciated (or misinterpreted.)

@howdydave sorry about that its just that mine was a bit of a joke. Just take the first letters of ship high in transit and you will get what I was getting at.

@Toque - I think you have it, good job!

“In short all goods seized by ‘Privateers’ were to be hence fourth referred to as “Spanish Prize” Goods. Spanish snuff was called “Spanish Prize” and all other goods were to be known as “Prize Goods””. Nice try, Roderick, but where does the text of 1786 actually say that looted snuff is specifically Spanish Prize or that Spanish Prize is specifically looted snuff? Spanish Prize is mentioned in English legislation referring to Prize Law long before snuff came into vogue. Goods and money looted from authorised privateers were deemed Prizes and their disposition subject to Prize Law including tax. Spanish Prize might include snuff, but also included plenty of other commodities as well. The text distinguishes between IMPORTATION of snuff and other goods such as liquor seized by privateers and is dealt with under separate clauses. Investigating further - the acts referred to in the text as passed in the “eighteenth Year of his present Majesty’s Reign” refers to declaration of war by France (1778) and Spain (1779) upon Britain and British authorisation of state approved piracy. Looking at the earlier Statute at Large “Spanish Prize” is defined simply as ships, vessels, and goods, belonging to the King of Spain with no mention of snuff. “Seven hundred and seventy-nine, was pleased to order that general Reprizals be granted against 'the Ships, Goods, and Subjects of the King of Spain; and that, as well all his Majesty’s Fleets and 'Ships, as also all other Ships and Vessels that shall be commissioned by Letters of Marque or General Reprizals, or otherwise, by the Commissioners for executing the Office of Lord High Admiral of Great 'Britain, shall and may lawfully seize all Ships, Vessels, and Goods, belonging to the King of Spain.” Leaving aside the meaning of S.P for a moment the question remains as to when the snuff appellation was first used. There are many references to Hardham’s, Princes, Lundy, Scotch and Kendal Brown in 19th century texts but no mention of S.P, which is curious. This suggests that S.P, sold under that label, was a provincial snuff, unknown outside Sheffield and its environs until the early 20th century. Searching the National Archives online there is, however, a business letter dated 21 November 1840 to J&H Wilsons in which a certain E. Stanley, Hulme orders S.P. Scotch and Princess and Morton’s Mixture. This is the earliest reference to S.P snuff I’ve ever come across and, as expected, is linked to Sheffield. The archives also reveal that Illingworth’s Snuffs Ltd. paid J&H Wilsons commission from 1932 for sales of ‘Best S.P’ made according to a formula devised by Mr. Harland (whoever he may have been). This supports the widely held opinion that S.P is a Sheffield snuff - as native to that grey town as its celebrated steel - and made by other manufacturers elsewhere under license. The debate goes on …

Well, you guys go ahead and debate, but the next time a new snuff user asks me what SP stands for, I’ll probably just give the old disclaimer of, “no one’s really sure, BUT…” and then point them to Rod’s evidence. It sounds reasonable and after all, in a debate, it very rarely ever falls to hard facts (since there aren’t any), but simply the most compelling credible evidence. And besides, it makes my brain hurt… :^)

I’m just going to tell people it means ‘Smells Purdy’ and blame it on Pensyltucky, my favorite fictitious state. If they backsass me, I’ll pound them through a knothole. Amen.

Sorry this passage is so long but, it makes fascinating reading. The crucial wording is in the second last sentence. The Port St. Mary and Vigo plunder show to what an enormous extent snuff was used in Spain, probably with France sharing. The fleet having returned to England, the officers and men set about selling their snuff, of which they had a weight approximating 100 tons. They called it Vigo Snuff or Vigo Prize Snuff, the word " prize " indicating that it had been captured by our ships. This greatly appealed to English admirers of the venturous. There was scarcely a town in England which these excellent snuffs, divorced from their buffalo skins, did not reach. The great impetus given to snuff-taking by these " prizes " established it as firmly in England as it was on the Continent. It has been said that snuff-taking really began on the grand scale in the reign of Queen Anne. One of the reasons for this clearly emerges from the foregoing story; Queen Anne’s accession and the Vigo exploits both occurred in 1702. We have no means of knowing just how the Vigo snuff was treated when it reached this country or to whom the officers and men sold their share. It seems likely that much of it was taken by blenders and ultimately mixed and per- fumed so that all tastes were in the end suited. At this point, snuff’s history seems to divide itself, so we will take a couple of pinches ourselves, and start a new chapter on the elegant age of snuff. CHAPTER II The Elegant Age " Who takes thee not? Where’er I range I smell they sweets Jrom Pall Mu/l to the 'Change•." JAMCS BOSWL°LL, 1740. B Y 1702, when Queen Anne came to the Throne, smoking had had more than a century of supremacy. It had successfully kept snuff largely within the conlines of the elite, and, until that year, there was nothing to indicate that things would change very much. Then came the avalanche of Vigo and Port St. Mary snuff described in our last chapter. A writer of the period said there was a positive haze of snuff over Plymouth when Admiral Rooke’s ships were unloading, and that " there was much sneezing among the people." In approaching the second period of snuff’s history, we have to view it on two planes-the high and the low, the patrician and the plebeian. There is not a great deal to be said about the latter. It provided no fabulously elegant snuff-boxes, and inspired no poets, with the possible exception of Rabbie Burns. Snuff did, however, find its way into industries where smoking was forbidden, now that its price was within reach of the workers. Among the trades which took up snuff were printing and tailoring, and snuff-taking still persists in them. Other industries followed suit for no obvious reason except that the workers liked snuff, found it cheaper than tobacco, and easier to use at work. Rapidly the habit spread far and wide. Obviously the immense stocks of Spanish " prize " snuff could not last indefinitely, although many merchants who bought it from the sailors locked it up and released it piece- meal when they deemed it profitable. Meanwhile it was clear that a new and enormous trade had arisen. Our imports of tobacco leaf grew accordingly, just as snuff-mills were to multiply and increase in size.

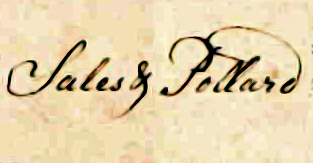

“That history also refers to the older snuffs having been made from unadulterated tobaccos, so presumably a bergamot-scented snuff in the 18th century would have been sufficiently unusual to be notable.” Vathek - Perhaps, although the earliest reference to bergamot (burgamet ) snuff, according to ‘The Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities : 1550-1820‘, is dated 1706. The same source also describes Spanish snuff, which was sold simply as Spanish. The feature of Spanish snuff was that (unlike Scotch) it contained no stalk, and was not rappee (meaning fermented as opposed to simply coarse). The description is PLAIN - i.e unscented. Some 18th century snuffs were scented (as well as unscented) as evidenced by Charles Lille in “The British Perfumer” - a fascinating contemporary read of a bygone snuff age. S.P is not mentioned anywhere in the text. ****************************************** Now, to throw a large spanner in the S.P works - In the ‘Directory of London and Westminster, & Borough of Southwark1794’ a tobacconist shop Sales & Pollard, Tobacconists, 72, Aldersgate-street is listed. Research proves that they set up shop back in 1750 and were snuff manufacturers. Now, this confuses ’The Great Question’ further as it is claimed in “Tobacco Whiffs for the Smoking Carriage” of 1874 that S.P snuff is named after Sales & Pollard before they were renamed Sales, Pollard & Lloyd, moving to Farringdon Street in 1871 - “Among the specialities manufactured by the firm, so often mentioned in this chapter, is the " SP" Scotch snuff, originally manufactured when the house was known only as Sales & Pollard, the initial letters of which names were used …” Frustratingly I’ll have to buy the book as the damned site won’t allow me to read more. But there, in black and white, is the (possible) answer to snuff’s greatest conundrum. S.P = Sales & Pollard IF they were selling their snuff as early as 1750 then this is prior to the time Wilson’s claim they were making S.P. The question remains: When did Wilson’s of Sharrow start manufacturing snuff sold as S.P? If S.P was manufactured under that name by Sharrow prior to 1750 then the Sales & Pollard claim can be discounted. Not sure how much benefit would accrue from getting accreditation and visiting the archives held in Sheffield as snuff records are limited to J&H Wilsons and only go back as far as 1833. The records really worth viewing are those of Wilsons of Sharrow, which are private. I’ll see what I can do.

Unfortunately the author (C.W Shepherd in Snuff: Yesterday and Today) only refers to “Spanish " prize " snuff” in the context of the Vigo raid. Association with snuff manufactured as S.P by the reader is convenient, possibly real, but still only questionable inference, and not hard fact.

See this 19th century advertisement: " The initials of the firm (Sales & Pollard) have been adopted as the name of a very popular Snuff, thereby proving the high repute of the house as Snuff Makers" http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/evanion/FullImage.aspx?EvanID=024-000004382&ImageId=52011

So far, my favorite is “Smells Purdy”…

The Pollard Claim Questioned. Here is a trade-mark case of 1878. 62O. Ex parte Sales Pollard & Co. [T. M. A. 1875]. July 8, 1878. Jessel, M. R. “ON motion by the registered proprietors of a trade-mark on snuff, consisting of the letters " S. P.” (the initials of the firm), which they had discovered, subsequently to registration, to have been in common use for many years in the snuff trade, though used originally by themselves : Leave given to rectify the register by striking out the mark in question. " http://www.ebooksread.com/authors-eng/rowland-cox/a-manual-of-trade-mark-cases--comprising-sebastians-digest-of-trade-mark-cases-ala/page-30-a-manual-of-trade-mark-cases--comprising-sebastians-digest-of-trade-mark-cases-ala.shtml

PhilipS, I thought you argument was excellent and I really thought you might have found something we’d all missed. Hard luck! I suppose it could be likened to a company called Micro & Soft trying to register the Trade-Mark “Microsoft”.

Roderick - we don’t know (as yet) when Sales & Pollard started using S.P although, of course, they couldn’t register it themselves as a trademark in 1878 for the reason given. The law, as I understand it, is first to register as opposed to first to use. The next task is to see, if possible, whether Sharrow has also attempted a trade-mark on S.P and been refused for the same reason.

Thanks Philips once again for that interesting information. I have the Complete Oxford English Dictionary in microprint. It’s a good read under snuff with much interesting material. It mentions Spanish and Italian sorts sold under those names by English merchants very early on. No reference or clue as to SP under ‘Snuff’ though. Under the lengthy and detailed entries under ‘Spanish’, we find just one tiny, but perhaps telling reference to snuff: ‘Spanish snuff, usually PLAIN SPANISH obs.’ My money at this point is on ‘Spanish Plain’. Surely the idea of plain has occurred to everyone - but it is seems significant that the OED in its only Spanish reference to snuff links it to the word ‘Plain’. Apologies if this is either obvious or disappointing to anyone.

I heard that SP was short for Special Plain … ? No idea if that is correct or not lol, but it made good sense to me

Wouldn’t Special Plain be something of an oxymoron, though @MikeMoose? Surely, those are two mutually exclusive categories.

LOL, now that you mention it, that makes more sense than Special Plain . DAMN… I thought I had it all figured out

The Sales & Pollard trade-mark case over S.P snuff is cited in ‘The Yale Law Journal - Volume 20 No.1’ of 1910 as an example of terms held publici jurus. The text explains that - “Publici jurus words frequently used by tradesmen in a certain line of goods are said to be common to the trade. Of course, the true test is whether the use of the word “has ceased to deceive the public” as to the maker of the article and whether the word is current in the market amongst those “who are more or less directly connected with the use of the commodity to which the word is applied”. “Where three people use the name and at least two of them innocently, there is no proprietorship.” http://www.jstor.org/stable/785041?seq=7 The most telling words are - “the true test is whether the use of the word “has ceased to deceive the public” as to the maker of the article.” If the public was sufficiently deceived in 1878, the year of the S.P snuff case, then it is unlikely to become enlightened in 2011. Why couldn’t the idiot who started the manufacture of S.P have used a proper name instead of bloody letters! Take your pick - SP(anish) Spanish Prize Spanish Plain Sharrow P(lain)? Sheffield Pride Sales & Pollard Sed Paulatim Senatus Populus Smells Purdy Self Propelling etc …

I like Spanish plain however, Spanish was “prized” over any other snuff. In George the thirds reign snuffs were known by their country. Spanish French Italian Etc,etc…

The Sharrow Mills website says that Joseph Wilson started making SP in 1760.

Good find Juxtaposer. That pre-dates a lot.

Unfortunately there is no detail or citation, or date given for ‘Plain Spanish’. That OED is a bit of a rush job isn’t it. ‘Plain Spanish’ was at some stage a usual description of a known sort, or so it appears. The English maunfacturers would’nt want the abbreviation ‘PS’ on their vats and bottles, that would be untidy - It then became Spanish Plain (SP) rather than Plain Spanish. I would expect Plain Spanish to be have been around from the earliest times. (I see that the Irish and Scots used snuff before it became popular in England (around 1680 according to the OED). Scottish Plain or Scotch Plain might not be wrong. Mutter mutter mutter.) Is there such a link between Scotch snuffs and SP? I’ll stick with Plain Spanish and now I will correct people when they say ‘SP’. I’ll say ‘Shouldn’t that be PS?’

‘Plain Spanish don’t ye know’.

it’s a joke about spainards. Even the plain ones smell like citrus.

Outrageous remark. Don’t be so callous about lemons! Let me put you straight fellow snuffer - Rule#17-5.3-'Treatment of Lemons.

LOL! @bob & @petersuki Great thread everyone this is very interesting! Making history!

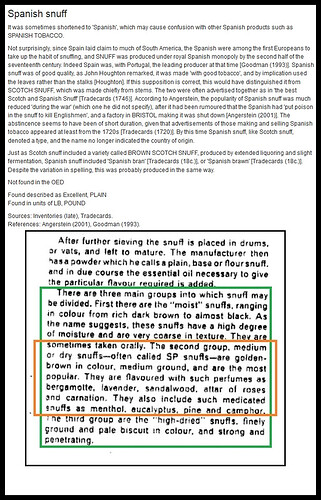

“‘Plain Spanish’ was at some stage a usual description of a known sort, or so it appears. The English maunfacturers would’nt want the abbreviation ‘PS’ on their vats and bottles, that would be untidy - It then became Spanish Plain (SP) rather than Plain Spanish.” The same reasoning occurred to me also. The hypothesis also stands up to scrutiny. **************************************************************************** “‘Plain Spanish’ was at some stage a usual description of a known sort -” **************************************************************************** Indeed, and there are plenty of sources to confirm this statement: http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=0lPJIuJ-vRYC&pg=PA200&lpg=PA200&dq=“Plain+Spanish”+snuff&source=bl&ots=n7erUxYxaa&sig=zJmeq9Ir4L8RUBLIpcrsvzwEu7E&hl=en http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=AsMIAAAAQAAJ&pg=RA2-PA70&lpg=RA2-PA70&dq=“Plain+Spanish”+snuff&source=bl&ots=384VHewS4V&sig=f\\_lpK43dJeCb9tuBY2Gf78du6zI&hl=en Plain Spanish (as opposed to just Spanish) was probably introduced to distinguish it from Spanish Bran. Evidence for this is provided below. “Just as Scotch snuff included a variety called BROWN SCOTCH SNUFF, produced by extended liquoring and slight fermentation, Spanish snuff included ‘Spanish bran’ [Tradecards (18c.)], or ‘Spanish brawn’ [Tradecards (18c.)]. Despite the variation in spelling, this was probably produced in the same way.” http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=58878 *********************************************************************************************** “The English maunfacturers would’nt want the abbreviation ‘PS’ on their vats and bottles.” *********************************************************************************************** Right again. No manufacturer is likely to use PS as a snuff abbreviation. One can imagine the lewd 18th century laughter at the request “Pass the PS pot”. Given that we now know S.P to be publici jurus, I’d say that ‘Spanish Plain’ is the strongest contester in this investigation to date.

Assuming S.P = Spanish Plain … Plain Spanish was evidently an unscented flour made from leaf tobacco (as opposed to Scotch, made from stalk). Over time manufacturers probably changed the snuff name with adulteration, leaving only diehards clinging to the S.P label. We know that Bergamot Snuff is very old. Perhaps certain S.Ps were adulterated as per Bergamot Snuff from Spain, but the S.P label remained unaltered to appeal to conservative taste. If this is the case then only a very few manufacturers still used the S.P label into the 19th century since references to it are almost non-existent. (The only 19th century references I’ve found so far are cited above.)

We also know that the best Spanish snuff was flavoured with bergamot and was “prized” by the earlier more elite snuff takers. Personally I like ‘Scottish Plain’ best!

Once again, Philips, thanks for this information. We agree then that '‘Plain’ Spanish can have come early with bergamot and perhaps citrus. If so It would have certainly been treated in this way before it came to these shores and its recipe would have been known, of course to the Spanish, and not necessarily to the English merchants. It was certainly much appreciated, but, would the bergamot have been recognised for what it was, in those early days? Perhaps people supposed that it was an intrinsic characteristic of the excellent plain Spanish tobacco. It was, perhaps, also considered Plain in comparison with other early sorts such as the ‘Italian’, which the OED mentions in the same breath. This, as I guess, would have been a much more highly scented variety. Can it really be that when we enjoy the quintessentially English SP, we are snuffing the closest thing we have to the ancient Spanish Plain. What a shocking thought!

OT - I’d recommend the entries in the OED as an excellent primer to any general reading around snuff. There are as usual many quotations and threads to follow. It’s not perfect, but it is the best there is. Have you room in house for the thirty odd large volumes? Is the two volume micro-print edition still available? Those who hanker after historical references to snuff in literature will be well on your way. One last. Snuff-Mundungus/ dungo/etc gets several mentions. Mundungus is defined as Tripe, Black Pudding, Offal, Refuse. As I see it a noisome black snuff, perhaps of the poorest quality (and possibly the highest strength). I believe it likely that at one time you could walk into a suitably down-market snuff shop and ask for a quarter ounce of Mundungus. Now, I dare any of you, excellent producers, and purveyers of the good stuff to produce a true Mundungus for us. I’d give it a go! Can I see a Toque Mundungus approaching?

They want money for that.

"Can it really be that when we enjoy the quintessentially English SP, we are snuffing the closest thing we have to the ancient Spanish Plain. What a shocking thought! " Who knows for sure? However, whatever S.P or SP stands for it should have the following characteristics: Colour - light or golden brown only Mill - no coarser than demigros Moisture - medium dry Flavour - the pungency derives from unscented tobacco. It may, however, be complemented by hints of the Citrus of Bergamia and lavender. That, for what it’s worth, is my view.

Finding definite proof that SP is Spanish (or anything else) is like looking for corn in Egypt in the lean years. Many brave souls have previously undertaken the mighty task and returned defeated. The more stubborn have condemned themselves, like the Flying Dutchman, to sail the wild and wasteful ocean for eternity without ever making port. Many have gone mad in the process and suicide is common. Nevertheless, I’m going to subscribe to the OED in one last forlorn hope.

Good luck!

The OED is the ultimate browsing delight. I’ll stick with the fact that the early (and somewhat later) existence of a Plain Spanish is highly suggestive of the later SP (Spanish Plain). Though those of us who have tracked etymologies for pleasure on occassion are too familiar with the twists and turns, dead ends and sudden insights this particular pass-time delivers. Something like knowledge is gained, but little or perhaps nothing in the way of certainty. Toque - you are missing your opportunity. I see an SG Mundungo on on the horizon. What better way of using up the bits that are just not fit for finer useage?

Sp is short for ‘Spanish’? ‘Spanish Prize?’ Don’t be silly, it stands for ‘Superlative Powder’ :o)

My heart is with you, - my head says ‘No’

So I skimmed through most of this conversation (as the last time I had read this thread 85 new posts have been posted) I wonder (and this is just me thinking, feel free to disagree or prove me wrong) If SP stands for Spanish Port? Meaning that I’m sure Spain was trading with a wide variety of countries, and so I wonder if they didn’t brand the barrels of snuff as to the destination of the snuff, that being a Spanish sea port. I also wonder if people back then thought that bergamot and lemon would keep the snuff fresher on a long sea voyage, and perhaps that’s why it has those flavors in it, not to scent it by any means, but as a way to preserve the snuff. If this was the case then by all means the snuff should be considered plain because the scents are only that of preserving the snuff for transportation and not necessarily for consumption.

@ourlastdefeat I disagree with your “skimming” through most of this conversation.

To what extent Juxtaposer? I know that for the most part in the discussion most people decided on Spanish Plain, and interjected the possibility that it was originally possibly named for Plain Spanish but the abbreviation posed a problem so they switched the words around to give the abbreviation of SP. The parts that I skimmed were the kind of long historical quotes from different sources and some of the responses to those posts, and some of the shorter responses I just skipped altogether.

The extent of my disagreement relates directly to the hours of research that some of us including myself have spent on this subject. I really should have put in a smiley face or an lol but I try not to use that language. Can you see the humor in my previous comment now?

Haha, yes I can, I thought it might have been a joke but I wanted to make sure. Also I applaud your efforts to not dumb down the English language I wish more people on the internet in general would do that at well but it is what is I suppose. At any rate I wanted to ask is there any factual evidence for my hypothesis about bergamot and lemon being used as a type of preservative for the transportation, and not necessarily for the consumption, of the snuff?

I can find no evidence of bergamot being used as a preservative for anything. What a did find is it being used as a thickener. Specifically a plot thickener, as in “the plot thickens”. What I found was the calling of the bergamot fruit a pear. P as in pear you see. Sharrow Pear hahahaha ludicrous you say? I tend to agree. I’m loosing sleep over this I’ll admit.

An argument against S.P. having to do with Spanish would be the Sheffield mills manufacturing of snuff. Spanish snuff was manufactured in Spain. If snuff was manufactured in Sheffield why would it be labeled Spanish?

For the same reason we call them French Fries? lol

Because they began quite naturally to produce their own version, or ‘take’ on the original and authentic Plain Spanish, perhaps, and this came to be called Spanish Plain (for the reason suggested, that is that PS was already taken, and as Philips points out it would be ludicrous on pots, and perhaps for also for other colloquial liguistic reasons (we have Spanish Leather, Spanish Fly, various other ‘Spanish things’, some better not mentioned)why not Spanish Plain, abbreviated naturally to SP? (The question mark here denotes ‘mere conjecture’.) ‘Spanish Plain’ is an excellent pedigree name for a snuff made from Havana leaf flavoured with bergamot, and produced as a normal SP, if there is such a thing. Who will snap it up? Toque - this might prove more popular than Mundungus! Would it cost a bomb?

Sorry, that fine snuff would be called Plain Spanish. Not Spanish Plain. I’m getting confused. I suppose it would be costly since anything that grows in Cuba is turned into a cigar, and these are pricey items. A suitably understated name for the costliest snuff around. Very ‘easy’ on the bergamot though, just a hint perhaps. I don’t think people from the US would be allowed to sample it though, unless things have changed. Havana SP.

“An argument against S.P. having to do with Spanish would be the Sheffield mills manufacturing of snuff.” Anyone taking snuff in the 1960s and before would remember that most Sharrow snuffs were labelled S.X. My earliest list shows: S.P S.S S.W (Sharrow Wallflower S.M (Sharrow Medicated) S.C (Sharrow Carnation) S.J (Sharrow Jockey Club) S.L (Sharrow Lavender) S.T (Sharrow Tonquin) I tentatively suggested before that S could stand for Sharrow (as in Sharrow Wallflower), and that the qualifiers for S.P and S.S have been lost. There are a number of arguments against this hypothesis. 1. There have been many hundreds of snuff mills and snuff chandlers over the centuries We only have scanty records for the very few mills that have survived and therefore tend to associate the etymology of S.P with those survivors. 2. Even Mark Chaytor, the greatest expert on snuff manufacture in Sheffield in general and Sharrow in particular, doesn’t know the origin of S.P for sure (which isn’t reassuring for amateur sleuths). 3. The Sales & Pollard case proves that S.P cannot be associated with any manufacturer in particular. “Spanish snuff was manufactured in Spain. If snuff was manufactured in Sheffield why would it be labeled Spanish? “ A good point. The answer is found in ‘The Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities : 1550-1820’ The text explains that: “Snuffs were available in the shops in great variety, many types apparently denoting a town or country of origin, like BARCELONA SNUFF, HAVANA SNUFF, PORTUGAL SNUFF, SCOTCH SNUFF and SPANISH SNUFF, though most of these during the eighteenth century came to denote a type rather than a place of origin. Others, like BERGAMOT SNUFF and ORANGERY SNUFF indicated a principal flavouring or perfume.” http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=58876#s6 Another question concerns the use of a period in the appellation. S.P suggests two words whereas SP is more likely to be just one. The earliest references I’ve seen are all S.P. Sharrow have only fairly recently started using SP and other manufacturers still use S.P. This supports the conjecture that S.P refers to two words and was possibly used after manufacture of Spanish style snuff commenced in Britain using leaf tobacco imported from her own American colonies in imitation.

“SP stands for Spanish Port? Meaning that I’m sure Spain was trading with a wide variety of countries, and so I wonder if they didn’t brand the barrels of snuff as to the destination of the snuff, that being a Spanish sea port.” No. Snuff production in Spain, like France was a royal monopoly. With the exception of contraband Spain did not import snuff - it exported it. ‘History of my life, Volumes 9-10’ By Giacomo Casanova (pages 308-309) provides an amusing observation on this point.

The Scene - A Good Snuff Shop, in or nearby the City of London, circa 1700 (or whenever). Customer: I wish to speak with you concerning this snuff I purchased here a week ago. Snuffman: Indeed sir, and how may I be of assistance? Customer: Well, some while ago a good friend of mine gave me a gift of some Plain Sanish. I found it VERY good. I came here with the intention of getting some more of it. Snuffman: Indeed, sir. Customer: I find that what you have given me is, although good indeed, however not quite similar. Snuffman: I think that sir will find that what he has purchased is Spanish Plain. It is a product of our own devising and shares many of the characterstics of the Plain Spanish. It has the virtue sir, of being produced in our very own English mills, not far off in the countryside, around Mitcham; if sir is acquainted with that area. Customer: I see… Snuffman: We shall of course be able to obtain and supply the Plain Spanish sort but I would have to advise sir that it would be CONSIDERABLY more ex-pensive. Customer: Exactly how much more ex-pensive. Snuffman: *@#@~@ Customer: I see. Well, in any case, I find your Spanish Plain just as nice. May I have some more… Snuffman: Yes of course ,sir. Will, pass the SP.

@petersuki …O.K. then guess I will snuff some Spanish Gem instead of some Spanish Jewel. I just think maybe we should scratch some notes on a cave wall so that the future generations might understand what SG stands for. Dare I comment about history repeating itself. Why yes, I do.

Perhaps some brainstorming over S.S. might shed some light on S.P.

For some odd reason each time I take a pinch of WoS S.S snuff I can’t help but think of it meaning Secret Service…makes me feel like a secret agent or something haha.

OT (Tonka. I can buy a jar online for 2.50. Postage added is 4.50. £7 for a few tonka seems a bit much. I have quite a lot of relatively plain snuff I’d like to add a bean to. How do get your tonka, if you use them? Sorry to go OT but there’s a wealth of experience here.(I’ve tried McGahey at 50p a bean, but he’s not got back to me yet.))

@petersuki I buy tonka beans off ebay, they are used in wiccan magic I am told, so new age shops should have some. 1oz (about 25 beans) should set you back no more than £3, buy 3 packs to offset the postage of £3 and it should work out about 16p a bean.

Many Thanks Khalid.

Fanciful

@juxtaposer If, to begin with, it was recognised as being in the style of Spanish snuff I suppose.

As usual, best conjecture, and hang on to that until proved wrong. It’s all that can be reasonably done. Like everyone else I’d welcome something more certain. Sans Pareil seems fanciful in that I have not seen any reference to such a sort anywhere. If a reference was found then it would be something you could ride on. The fact that there was train of this name is a pretty guess for a snuffing anorak. Perhaps I’ll check under sans pareil in the OED. If under this there was, for example, ‘A variety of snuff popular in blahdeblah’, it’d be a worthwhile conjecture. If on the other hand no such sort is ANYWHERE recorded we might just as well go for, say, Sans Petrol (on the grounds that it was produced without the use of the combustion engine).

Vathek Very good! But if, as you say, San(s) Pareil was a recognised product I’d say you had a good conjecture, not more than this (see my comments above, where I considered this possibility). Unfortunately the matter is not quite settled. Yours is now, in my view, as I stated above, ‘a worthwhile conjecture’, as good as any probably, and you might have a bull’s eye. But on the other hand you may have a red herring. For instance it is by no means beyond the realms of possibilty that ‘SP’ pre-dates San(s) Pareil and this grandiose name was merely a commercial tactic by the firm you mention. I’d be interested to hear from Philips; his view on this. Meantime I’ll take a look at the sources you mention.

I think what Vathek is trying to tell us is that SP stands for Sociological (ex)Periment.

“As usual, best conjecture, and hang on to that until proved wrong. It’s all that can be reasonably done. Like everyone else I’d welcome something more certain.” Either my son or I will be visiting the private archives of Sharrow next year - date to be arranged with the vice chairman in January 2012. ‘The Wilsons of Sharrow: the snuff-makers of Sheffield’ by Mark Chaytor is the definitive history of the company, but I will be looking specifically for any clues in the earliest records from 1750 to throw light on the most perplexing mystery in snuff history. References to S.P prior in date to that held on the National Archive and codification (if any) of Sharrow’s earliest trade lists will also be sought, as will references to the less well known but equally baffling S.S mystery. Naturally anything else of interest will be noted and duly reported. Will also arrange an appointment to view the Sheffield Archives while I’m there for any clues from the Westbrook mill. The really interesting archives, of course, are Sharrow’s. I’ll open a separate thread detailing the results next year. In the meantime there’s time for a thorough course on 18th century palaeography, some new reading glasses and a large magnifying glass.

At least S.P,rich in variety, isn’t in danger of disappearance like the legendary Café Royal.

I think a call to Smith’s will provide you with access to Café Royal

Nice information,thanks Xander.

Mcgahey is the only tobacconist who advertises Smith’s Cafe Royal that I’ve found. I tried to get some Cardinal there once but he was oos. (Have to say I was disappointed with the Golden Cardinal when I went up to Charing Cross Rd to get it - and the price! I think Abbraxas is cheaper and is a much more interesting snuff - imho).

G. Smith & Sons (United Kingdom) (currently contract made by Gawith Hoggarth TT Ltd.) An independent tobacconist with its own range of snuffs. These in the past have been contracted made by either Samuel Gawith or Gawith Hoggarth or both. Storefront address: 74 Charing Cross Road, London WC2H 0BG Tel. 0207 836 7422 (domestic) 00 44 207 836 7422 (international)

^^From my FAQ entry. I can’t comment on the prices, but they supposedly do mail order. If you need some Golden Cardinal, I suggest trying Samuel Gawith’s Bouquet! The shop needs more visits to reform it to a proper snuff shop. If you’re in France or USA, then you should use your telephone.

This text from an American journal is the earliest reference to the meaning of S.P (SP) I’ve found so far, and for which there is no ambiguity. It’s still not a particularly old source, but it supports the Spanish theory. It’s taken from ‘Historical Collections of the Essex Institute (Volume 105) 1863’. Because its not a free eBook I can’t read the original source for the definition (which may be much older). “Spanish Snuff — snuff of Spanish origin. Also entered as Sp snuff, Span prize snuff, Spanish snuff, Spanish prize snuff.” The same source also describes Prize snuff as: “Prize snuff — a confusing term, could be tobacco captured from an enemy vessel. Could also be snuff “prized” to fit into a shipping container.” The ‘Sheffield Pride’ school is shaking on its foundations.

What does SP stand for?

“Spanish Prize.” Well done Philip. That has to be the best proof yet!

Collins Complete: Sp SP equals ‘Spanish’, That simple. More or less. I’m sticking to the British Isles’ take on Plan Spanish, or Spanish style snuff (maybe not so plain as supposed) for now. This enables me to make my tenous conjecture that the SP sort is among the oldest produced in the land. I’d assume that the original Plain Spanish, perhaps even the fabulous Prize was already milled (you might know better), and that the rasp came later, before the English/French mills got going. See the number of guesses here. The habit of rasping your own led to the taste for the later development of the coarser milled rappee sorts. All was complete when the English mill owners found they could use some of their capacity to mill cheaply, and yet to charge close to those astronmical Spanish prices. SP then stands for ‘relatively cheap to produce English snuff based on an originally Spanish flour, with a very tidy profit for the mills and shops.’

"SP then stands for ‘relatively cheap to produce English snuff based on an originally Spanish flour, with a very tidy profit for the mills and shops.’ " Petersuki - You’ve touched upon an interesting point. Tobacco growing has been prohibited in Britain since the reign of James I. Duty on imported tobacco was excessively high and almost ruined the economy of Virginia in the 17th century. Although contemporary records are confusing it is clear that by the 18th century preferential duty (but not a monopoly) was applied to tobacco grown in our own American colonies and it was from there, not Spanish colonies, that most of the crop was imported. British snuff exports during the same century and early 19th were rappee, Scotch and Brown Scotch and “Snuff work not hereinbefore enumerated or described“. I’ve scoured contemporary records on British manufactured goods for export and can only find reference to these four categories. Several decades after the union with Ireland in 1800 Lundy Foot snuff also appears in the list of manufactured snuffs exported abroad. Spanish snuff was imported into Britain in the 18th century - or in war, seized. Contemporary descriptions vary according to source and of course there was more than one Spanish snuff (just as there are plenty of British snuffs today.) According to generalised definitions, Spanish snuff is simply snuff manufactured in Spain from tobacco grown in the plantations of Spanish dominions - notably Cuba. If Spanish snuff is simply snuff from Spain then, at some point, the appellation was bestowed upon snuff manufactured in Britain whether or not the tobacco was grown on Spanish plantations. Statutes and journals repeatedly refer to “tobacco manufactured into what is commonly called or known by the name of Spanish.” What is not clear, however, is whether “Spanish” refers specifically to a blend with short-cut tobacco and exported as Short Cut Tobacco or snuff. Perhaps you or someone else can give an opinion on this matter by Googling Free eBooks for this quote… The question remains - what unequivocal evidence is there to show when snuff manufactured in Britain (rather than imported ready made from Spain) was made as either Spanish or S.P? It doesn’t appear in export lists so must have been, as you suggest, originally for domestic consumption only. Of interest, the oldest found source to describe S.P is from “Cope’s Tobacco Plant”.1870-1881 " In France, where, under the Imperial regime, snuff-making was a Government monopoly, the tobacco was allowed to ferment for twelve or eighteen months ; and in the principal factory (that at Strasburg) might have been seen scores of huge bins, as largo as porter vats, all piled up with tobacco in various stages of fermentation. The tobacco, after being fermented, if intended for that light, powdery, brown-looking snuff called S. P., is dried a little ; or if for Prince’s Mixture, Macobau, or any other kind of Rappee, is at once thrown into what is called the mull. The mull is a kind of large iron mortar …” This passage is quoted verbatim in ‘Tobacco: It’s history, varieties, culture, manufacture and commerce’ by E.R Billings in 1875. This again supports the Spanish theory as contemporary descriptions of imported Spanish snuff (Spanish Bran excepted) refer to it as being fin and not gros.

"Well done Philip. That has to be the best proof yet! " Yes, I was pleased to find it although it’s a pity the journal isn’t at least a century older. No 18th century dictionary, work on etymology or any other source mentions the meaning of S.P in the context of snuff at all. The earliest mention of the snuff is still only dated 1840.

Where was France getting their tobacco from?

Louisiana? Haiti? Macouba in Martinique? (Macouba is a district in Maritnique)

“The question remains - what unequivocal evidence is there to show when snuff manufactured in Britain (rather than imported ready made from Spain) was made as either Spanish or S.P?” The British Perfumer by Charles Lillie, edited by Colin Mackenzie answers this question. Lillie was writing in the early 18th century but his work was not edited and published until 1822. Snuff sold as S.P today bears little resemblance to the following descriptions of ‘Good English-Spanish‘ and ‘Worst Sort‘. As the two Wilson’s companies were the last survivors making S.P the snuff has simply become associated with their versions, which are now considered by many (including myself) to be the genuine article. This was clearly not always the case. We know the appellation S.P is deemed publici jurus and so anyone could manufacture snuff of any sort under the S.P label. My conclusion (based on the ‘Historical Collections of the Essex Institute (Volume 105) 1863’)) is that S.P stands for Spanish. The entry is unequivocal. Originally Spanish snuff was sold under that name from imported or seized Spanish snuff, but very early on was imitated in England and the counterfeit passed on to a domestic market as Spanish. It’s doubtful whether the S.Ps sold today bear much resemblance to any sort of 18th century Spanish snuff. Only the appellation now remains. **************************************************** GOOD ENGLISH-SPANISH SNUFF. A good and legitimate imitation of Spanish snuff, is made in London, with great success, as follows:— Take good unsifted bale snuff, and grind it down to a fine powder. If the tobacco be too strong, mix it with the fine powder of Spanish nut-shells, which is by far the best mixture (and not at all hurtful) which can be used. Over this sprinkle some water, in which a little treacle has been dissolved; and when, after mixing with the hands, it has lain in a heap for some days, to sweat and incorporate, pack it up; but, when doing this, take care that it be not too moist. Bemarks. This snuff, in the course of twelve months, will be of one uniform and agreeable flavour ; and will keep good, and mending, for more years, than the base stuff, before described, will months. When old, this sort will hardly be inferior to many of the plain snuffs made in Spain. LONDON IMITATIONS OF SPANISH SNUFF. WORST SORT. It is a very common custom in this country, to imitate the several sorts of Spanish snuff; but when the reader has perused the following account, he will be able to judge how far these are fair and just imitations. Havannah snuff, in bales and scrows, at the present period, comes to this country neat as ground down, without having any of its fine flavour taken from it. It may also be bought in great quantities, and very cheap; and it is consequently from this article, that our English-Spanish snuff ought to be made. If this was done with care and honesty, the imitation would undoubtedly be very good, and not inferior to the genuine article; whereas, the common sort is thus managed:— The fine powder, which is the best part of the whole, is sifted from the bale snuff; and the coarse and stalky part which is left, is ground down by a horse or water mill. This, however, is previously mixed with some strong cheap tobacco powder, with tobacco dust, which formerly used to be thrown into a common dust-cart, with that abominable vegetable called savine, and with brick-dust, common fine yellow sand, the sweepings of tobacconists’ shops and work-shops, old rotten wood, commonly called powder of post, and with many other filthy vegetable substances, both dry and green, to render the flavour whatever the dishonest compounder may wish it to be, and to pass it upon the consumer as the real flavour of tobacco. All or most of these ingredients being mixed into one body, they are now to be washed, as the next operation is technically termed. This is nothing more than colouring the filthy compound with red ochre, or umber, or other noxious red or brown colour, mixed with water and molasses!!! The whole, when properly incorporated, is now passed through a wire or hair sieve, to mix it more intimately; and is then left for some time to sweat, or become equally moist. This moistness is intended to imitate the oilyness (G—d help us !) which is peculiar to the real genuine Rancia from Havannah. This compound, or snuff, as it is called, is now packed up in barrels, tin canisters, and stone jars, in order that it may come out in lumps, like the Spanish snuffs. This is effected by hard pressure; and is done merely to deceive the ignorant purchaser, on whom this compound of dirt and filth is imposed, for real Spanish snuff, made from neat bale snuff from Havannah. Such is the composition of a very great part of what is made and sold in this town, for common Spanish snuff. Charles Lillie

Once again Philip, you continue to be an amazing wealth of information. ^:)^

no kidding

Jaap - Or you could try making the ‘Worst Sort’ by adding savine, brick-dust, common fine yellow sand, the sweepings of tobacconists’ shops and work-shops and old rotten wood. Make it as a scientific social experiment to see if people are as gullible now as they obviously were in the 18th century :<)

Just a further point of interest - Genuine Spanish, according to British History Online, used more leaf as opposed to Scotch which comprised more stalk. At some point in the first half of the 19th century the two types became intermingled, denoting neither a place of origin (Spain or Scotland) or even a specific type. Queen’s is a very old name on Wilson’s list (now sold as Queen‘s Extra Strong, with the old Queen’s sold as Best SP). It’s an SP but was advertised in the 19th century as a Scotch. How confusing! ‘The art of perfumery and the methods of obtaining the odours of plants’ by George William Septimus Piesse (1862) tells us that “Queen’s Scotch is flavoured with bergamot.” Indeed, George, it still is.

The question of what type of Spanish nut shells resurfaces here.

‘Perhaps you or someone else can give an opinion on this matter by Googling Free eBooks for this quote…’

Philips S.

I’ll see what I can do.

In any case, my mind, which is more easily set at rest that that of any professional historian or researcher, (though still curious), is more or less content with what you have generously provided.

Your recent findings are fascinating reading. My conjecture, having been to some extent informed by some of your comments here and on other threads, remains much the same for now.

The attempt to originate SP in t’north, is probably hopeless.

SP as an abbreviation must go back to or beyond the days when the English sailed the seven seas in more or less the same style as our own latter day Somalian pirates Their lists of booty may have read something like this - if they were lucky:

sp:Reales 50

sp: Dubloons 10

fr wine: 10 casks

sp snuff: 2 casks (‘What’s that?’ , ‘Snuff somer up your nose’ ‘Achoo’)

Perhaps even merchants in Chaucer’s day were listing their goods as sp this and sp that…

(Sans Pareil, although curiously enough a friend, whose memory I would trust, says that he recalls it from some thirty years ago (!), would be simply a marketing gimmick to cash in on the much older stuff and name)

Without anything solid to back it up I would guess that the Spanish Prize, was already milled. The fabled descriptions of clouds of snuff rising up over Plymouth or wherever seems to indicate that the stuff was already a fine powder. It would have taken a while to convince the mill owners in Britain, that there was good money to be made, and time to learn the techniques and so on. No doubt these early experiments were aimed at producing similitude to the Plain Spanish.

Meanwhile the rasp. Once this became the customary practice there would again in some quarters be a sort of conservative reaction against milled snuff, or a preference for the do it youself variety. But the great mills of Mitcham (which once, as I read, produced the bulk of London’s snuff), began to win against this practice. When did it finally disappear is another interesting question.

I somehow wonder if the Spanish themselves ever went through a rasp phase at all! And this appears to be another interesting question. Has anyone seen a Spanish snuff rasp?

Juxtaposer: What nut? Oh no not another ?. The Spanish didn’t have access to tonka did they…but not the shell? Ah well. Help!

(As another aside I see that F & T once produced a Mitcham Mint snuff. It is a sad fact that neither mint nor lavender are now grown commercially in Mitcham, nor is snuff produced there. I once listened to a French radio programme where it was acknowledged that ‘menthe de Mitcham’ is the best in the world. The French seem to know more about English herbs than the English do, dear oh dear. However, this does lead me to surmise that the minted snuffs have their origin here.) But would a London Brown, made in Mitcham be like…

The Victorian description you have provided: 'The tobacco, after being fermented, if intended for that light, powdery, brown-looking snuff called S. P., is dried a little…. is all so suggestive to me that I return to my hobby horse: if a snuff were made according to the SP method here described, using Havana leaf, we would in my view have recreated something like the early ‘Plain Spanish’. Though not perhaps the Plain Spanish of Alexander Pope, which I’d guess would more than likely be the suppositious English version, or proto-SP. And, as I’ve suggested, more than likely produced in Mitcham,Surrey. Far, sadly, from Sheffield.

Now I must stop guessing and see if I can find the EVIDENCE you were looking for.

What nut

I’ve been watching you all from the side because nobody asked ME what SP stands for. Now I feel it’s time to help you out of your predictament.

SP, of course, stands for Sir Pieter

@petersuki The nutshell powder to mix with tobacco to make the a “bastard” Spanish snuff of the “best sort”.

Pieter: haha. It’s time for you to explain everything. Best Wishes.

Juxtaposer: Yes I saw that. I mean, along with you, What was it?’ Not Tonka surely?

No, not tonka. I think almond shells. That would be my best guess. I forget what some of the other guys suggested the last time we discussed it. Anyhow when it first came up (last year I think) I took it as a recipe to make “Spanish snuff of the best sort”. But now, with more snuff making experience, I clearly read “imitation Spanish snuff” not of the “worst sort”.

HMM?

Nutmeg? : I had a little nut tree nothing would it bear but a silver nutmeg and a golden pear, The king of Spain’s daughter came to marry me, And all for the sake of my little nut tree.

I don’t like the stuff and would NOT buy a snuff with this ingredient. But our ancestors seem to have prized it hightly. No evidence for this guess whatsoever. Only for a laugh.

Would be mace if it were the shells…The only nut I know that produces another spice of its own shell.

Not the shell. The husk. But this might have been what they meant.

Summarizing all info into this post, up to this point: At this day, nobody knows certainly what SP stands for. We also ignore the first documents where SP designation appeared, supposedly used by clerks in record books. However, there are some clues that lead to several conclusions: – If " SP" designation stands for one word, then it seems to mean " spanish". – If it stands for two words ( S.P. ), then it seems to mean " Spanish Prize". If we rely on historical evidence, there are some antique documents that would proof the prior use of this name. – About other names: - Sheffield Proud/Plain - they seem to be more recent designations (final XIX - XX Centuries), a commercial attempt to put a end to this mistery, based on the Sheffield established factories that pioneered the making of Snuff in England. - Spanish Plain - If this would be true, then it should mean that there was a Spanish scented out there, and it´s not the case. - S.P. as acronym like S.M., C.M., K.B., etc- designations from some snuff makers, but the case is we know what every two letters stand for, except for S.P. (it does not make sense we know every other but not this only one, so this latter must be much older and obscured). Maybe, IMHO, a reason to use the S.P. designation was to hide someway the origin of this notorious sort to a growing number of new consumers in a rising empire: No reason for being proud that a british made snuff of certain success was coming from a Spanish Prize. A national successful product known as an imitation of looted foreign snuff doesn´t sound politically acceptable to Gentlemen (and wannabes) of a Great Empire! No way!. So, just as a supposition, maybe the tricky SP remained to name this sort of snuff. - Sales & Pollard - A commercial attempt to register SP snuff as a trademark, so, very much later than SP designation start. There goes my 2 cents; First, an historical intro: In Spain, after “Instruccion de 1684” by “Real Hacienda” (Royal Treasury), was stablished a state monopoly about tobacco throughout the Spanish Empire. This monopoly was short-lived, and suffered subsequent revisions after some more “Instrucciones”, but it established someway a lasting idea: All tobacco coming from Spanish territories abroad (La Habana, Trinidad de La Habana, Trinidad de Guayana, Puerto Rico y Santo Domingo) have to be brought to Seville, and the Tobacco Factory of Seville was the only authorized plant to manufacture snuff and cigars for the whole Spanish Empire and to trade with foreign countries. All tobacco coming to Seville must be raw tobacco, and was detailed and registered here by “La Real Casa de la Contratación”, the Spanish Royal Trade Agency. So the only tobacco products coming from La Habana were Leaf and “Polvomonte”, a coarse base snuff result of the first ground and sieve of Havana Leaf, that was meant to be further processed to become several fine sorts (although some quantities of “Polvomonte” were also sold as is in Spain). If the Vigo fleet was directly coming from La Habana, then the only snuff they carried was that gross “polvomonte”. This perfectly suits the story related by Charles Lillie in “The London Perfumer”, when he writes “It now came to the turn of sea-officers and sailors to be snuff propietors and merchants; for, at Vigo, they became posessed of prodigious quantities of gross snuff, from the Havannah, in bales, bags, and scrows, which were designed for manufacture in differents parts of Spain”.(p.295) Well, this latter part was not actually right. Officially there was only one facility in Spain to manufacture tobacco products, and it was the Royal Factory of Seville. However, it is known that, apart from the regulated market, there were some small shops throughout the peninsula that manufacture some small batches of products from smuggled tobacco, but they were mostly cigars. Before the lines about the Vigo attack, C. Lillie writes that “[…]Port of St. Mary and other adjacent places were plundered. Here, besides some very rich merchandize […] several thousand barrels and casks of fine snuffs were taken […]. Each of these contained four tin canisters of snuff of the best growth, and of the finest Spanish manufacture.”(p. 294-295). At that time, Port of St Mary was one of the most important trade ports of Spain, storing plentiful goods and merchandise. And the snuff stored there was the Sevillian Snuff in its several varieties, waiting to be exported or shipped to other spanish ports by merchants. – Why a gross plain snuff became essented with bergamot? In my opinion, there are two possible answers: +First, that being bergamot an essence used in perfumes and meals in Great Britain by then, at some point someone decided to add it to plain snuff either to enhance it or to disguise a bad quality product, +or second, that its use was a way to imitate the spanish finest snuff (sevillian snuff or “Polvo Sevillano Fino”) looted from Port of St. Mary (Puerto de Santa Maria, Cadiz). Why bergamot? Many streets and squares of Seville have a large number of bitter orange trees, that provide a distinctive orange blossom perfume in the air during Spring (and, by the way, the best sort of oranges to make the premium english marmalade). The finest sort of perfumed snuff from Seville used, among other ingredients, “almagre” (a kind of red earth or red ochre) to give it a characteristic colour and texture, and “agua de azahar” (orange blossom water, also known as neroli water). Bergamot has some similarity with orange blossom, and adds a citric tone similar to the intended product. Using this known ingredient, the resulting snuff may have a strong resemblance to that Sevillian sort. Also, knowing this last part, we can figure out where the recipe for F&T Seville derives from. But that is another story…

@Toque As King George was a native speaker of German his “Spanish Prize” may have also meant “Spanish Pinch”.

Simply Perfect

Another possibility: “Doctor J. N. Price of the University of Michigan who has made special study of the early days of Anglo-American tobacco trade recently suggested to the author that the initials signified nothing more romantic than “Scented & Perfumed”, a theory with which the author must rather reluctantly concur.”

And the winner is “Scented Plain”. Thank you and good night.

On a totally non serious note I propose we all make up our own meanings…i’m rocking Superb Powder there i said it.

I have a new theory! I have not read all of this thread though. Unless @Filek is right I think it’s possible SP is not English. What if its Latin or some other language? Just cause English Called it SP does not mean it is going to be an English word.

@Igglet, you should read the whole thread. There are a lot of fascinating theories here which should lead you to the truth. Btw the last of my posts was an accident at work - I was thinking about how Samuel Gawith might thinks about SP. No vodka involved. I don’t even like vodka

Who’s nose knows? I used to love “classic” SPs like Tom Buck, et. al. but after over use I began to tire of bergamot. I’m convinced it refers to the grind rather than the scent…I could be wrong, but as I’ve mentioned before, Samuel Gawith considers Firedance, Buck’s Fizz and the Crests as SPs, and there’s not a whiff of bergamot in the bunch. They’re not exactly late comers to the snuff game, so they might know something we don’t. It may be shorthand for “Shit Provoker” since it has provoked more than its fair share of shit debate here and elsewhere.

I read all of it shortly after I posted. If its English I think it is just Spanish. If it’s not, I have no clue. I only know English and, a lot of English Grammar Police would say poorly.

I have heard the arguments and I believe that no one knows what the hell SP means. So I have decided to suggest other possibilities for titles for this type of snuff. Take your pick. Snuff Plunder Senseless Puzzle Sly Pretense Slightly Perplexed Strange Passtime Subtle Proposition Silly & Pointless Stupid Politician Superficial Prattle Swindled Prospect Scathing Put-down Hmmm. It seems that I have too much time on my hands.

WoS make a “SP Menthol”. I have it. Im not quite sure what makes it different from any other menthol.

Here’s another theory - the English snuff mills never knew what it stood for. It seems ominous that the origin has been lost despite the wealth of knowledge that has been dug up on old snuffs. It seems more likely to me that SP was the name from the start. We do know that snuff was sometimes aquired as part of a haul or trophy from a victory, so what if one of those trophy barrels just said SP on it. Maybe it referred to what was in the barrel before the snuff, maybe it was a person’s initials or even a shipping code. The new owner, or one of his peers decides that barrel is their favourite snuff and charges one of his subordinates to get English makers to replicate it. “Get me some more of that SP batch made”. The name sticks, and the snuff becomes popular, and as the years roll by mills start adding their own taglines to give meaning to the initials hence the “Spanish Prize” and “Sheffield Pride” - effectively their brand names for their version of the original mysterious SP. Seems to me that any true etymology for the term would have been discovered by now in some of the old texts and historical records. The snuff always having been called SP through inherittance rather than being an anagram seems more likely to me somehow.

“Viking Blonde snuff is made from high quality flue cured bright Virginia leaf. It is a medium fine ground plain SP style snuff, light brown in colour and moist.” From this and other resources I can only surmise that the term ‘SP’ doesn’t mean a thing. The bergamot, etc that some insist is mandatory for an SP to be an SP may be correct. Research proves otherwise. That said I *repeat myself again: St. Casura is the ultimate SP. *As Chairman of the Department of Redundancy Department Chairman

_

That said I *repeat myself again: St. Casura is the ultimate SP.*As Chairman of the Department of Redundancy Department Chairman_

Jaxons SP Premium, M&W Jocks Choice and Toque Berwick Brown (well aired) for me

That said I *repeat myself again: St. Casura is the ultimate SP.

I agree completely @ChefDaniel. St. Casura is the best SP I have had as well.

there is a possibility that could mean “spanish pride” which is what i like to think it means

Spanish

“SP”. This blend obtained its name through a naval battle off the shore of a Spanish port, Vigo, in 1702. The French fleet was protecting a rich Spanish convoy of galleons which had sailed from the West Indies when a combined English and Dutch fleet under Admiral Sir George Rooke attacked. One ship, the Torbay, under the command of Vice-Admiral Hobson was becalmed and trapped in a most compromising position. A contemporary chronicler writes, “All this while Admiral Hobson was in extreme danger; for being clapt on board by a French Fireship, whereby his rigging was presently set on fire, he expected every moment to be burnt; but it very fortunately fell out that the French ship, which indeed was a Merchantman laden with snuff, and fitted up in haste for a Fireship, being blown up, the snuff, in some measure extinguished the fire, and preserved the English Man of War from being consumed.” This battle, for which Hobson received a Knighthood and a pension of £500, was largely responsible for starting the popular fashion of snuff-taking in England. The booty from the captured Spanish galleons included a large quantity of snuff which was subsequently sold in London. Referred to as “Spanish” by the clerks, they soon abbreviated this to “SP”, thus originating the name of the most popular blend of all.

@Roderick You are right. Spanish snuff was named “Polvo” o “Tabaco polvo”. Manufactured in Seville -Sevilla in spanish (pronounced “Sabillia” by an english speaking person)-, its most renowned sort, commonly known as “Polvo Sevillano” o “Polvo de Sevilla”, enjoyed great fame in France throughout XVIII Century. But it´s not surprising that there are references of this snuff during XVII Century in Scotland, as Scotland and Spain once were strategic allies against “la Pérfida Albión” (England), and had maintained close political and trade relations some decades before.