Tom Buck is possibly after Tom ‘Buck’ Whaley but there is no direct evidence to support this possibility beyond the nickname to signify a robust, fashionable, and spirited young man who died in 1800. This was a suggestion of mine, not to be taken as fact. Nicotiana persica or ‘tombak’ from Persia, also known as Shiraz from the area where it was most prevalent is a viable suggestion having the double advantage of being both a tobacco and having name similarity: easy to corrupt tombak to Tom Buck. This was first suggested, I believe, by the poster ermtony.

Some ten-fifteen years ago when the origin of the name was discussed on Snuffhouse my first thought was of a manufacturer trading under the name of Thomas Buck. Back then and more recently I made diligent searches of late 18th and early 19th century trade directories, and although the name appears there is no association of that name with tobacco.

If not satisfied with the first two options then a viable possibility is that the snuff is named after a patron of a particular manufacturer who requested a stronger version of Queens or is named after an employee of that manufacturer who came up with the original formula. Or it could just have been conjured up on a whim and fancy. Any suggestions from snuff historians welcome.

Unfortunately there is no evidence to support the tombak claim either.

Is anyone able to find UK import records for tobaccos that include Shiraz tobacco or Nicotiana persica or tombak? I can’t. The earliest record in English that I can find dates from 1826 - ‘The Botanic Garden: Ornamental Flowering Plants’ by B. Maund. The earliest reference to Shiraz tobacco I could find is dated 1833. All these early references concern Nicotiana persica as an ornamental flowering plant rather than importation of bales of tobacco like Virginia or Kentucky.

The earliest record I could find for smoking tombak is Habits, Manners and Customs of All Nations dated 1830. There is no mention of its exportation.

The Indian Forester-Volume 18 from the year 1892 tells that around 1,500-2,000 bales of tombak are produced annually and that these are largely consumed by members of the Imperial family who appear to smoke their water pipes all day…

I don’t know when Sales & Pollard first made Tom Buck as, infuriatingly, nothing is dated except for an account book up to 1838. I didn’t photograph all the pages, but those few I did make no mention of the tobacco in question (for what it’s worth). It is a fact, however, that Sharrow introduced Tom Buck in 1844 and that the larger London business probably made it earlier. This is dangerously close to earliest English references to tombak/Nicotiana persica.

Attractive and plausible as the tombak theory is I doubt it is the origin of the name Tom Buck.

I suspect I was brought to the board because I was doing a revisit last year regarding theories relating to Tom Buck. Unfortunately, both theories have their flaws, although the scales definitely tip in favor of Persian tobacco. However, I am surprised why you avoid this particular phrase in your search, looking for more refined ones, because the searches will definitely go below 1826. Basically, when making this revisit, I did not focus on the word “tombak” (although it was the starting point), but “Persian tobacco” and possible way of getting it to Europe. I will be at a loss here at the moment, because I will not provide any source, but there was such a route - namely through Syria it was distributed in the Mediterranean Sea. I also randomly checked in several languages the possibility of knowing the word “tombac” or Persian tobacco, perhaps for French, German and Hungarian, which technically shows that tobacco itself was known in continental Europe. However, I must agree that I have not found such knowledge for Great Britain when it comes to the possible export of this tobacco to this country in the period from the second half of the 18th century to the beginning of the 19th century. Basically, I believe the name “Tom Buck” comes from the word “tombak”, albeit merely as a pun. To some extent, this idea would be confirmed by other producers of this snuff, who included “Tombuck” spelled together in their offer, although I did not find anything below the year 1860 with this name, so it is not any confirmation.

I can’t say anything about Tom ‘Buck’ Whaley, or another Thomas Buck, as I haven’t come across any references that suggest any connection with tobacco.

Thank you for your interesting reply.

My understanding is that tombak is specifically Nicotiana persica, also known (less reliably) as Shriaz after the area where it was mainly cultivated. I avoided using ‘Persian tobacco’ because not all tobacco grown in Persia in the first half of the 19th century was tombak.

Sir Henry Willcock, was the British envoy in Persia from 1815-1826, and it was he who later brought back seeds of tombak for presentation to the Royal Horticultural Society c.1831 as an ornamental flowering plant. .

I’m not saying that Tom Buck is not after tombak but the name in Britain, it seems, was completely unknown except to the Horticultural Society and accounts by travellers after 1830 - much less using the tobacco itself. But perhaps a director reading one of these accounts came across the name tombak and decided to use it for a more strongly flavoured Queen’s Scotch. Who knows for sure!

It seems to me that the average consumer was not that interested in Latin naming details, hence the colloquial term “tombak” for “Persian tobacco”. Therefore, for me, a linguistic approach to the topic seems to be the most logical at this point, because while tobacco itself could not have reached Great Britain at that time, the word “tombak” itself could have, for example, through trade contacts or sailors. Hence the heard “Tombuck”. Unfortunately, as you mention, the lack of such a denunciation in written form makes it difficult to confirm this thesis.

I could add here the same thing that I think about the case of “Grand Cairo”, i.e. a name related to marketing purposes. “Tom Buck”, as I understand it, was created in the same period, which may also suggest an attempt to interest its products in people who are beginning to be interested in oriental culture. And I think it would be an extraordinary courtesy from the first manufacturer of this snuff, who did not deceive his customers by selling “Tombac”, but the recently heard “Tom Buck”.

Research throws up some interesting characters, for example the 18th century pugilist Tom Buck who regularly fought with fists, broadswords, cudgels and quarterstaff at the London amphitheatre of James Figg.

Another 18th century Tom Buck (Tory Tom) was one famed for his prolific consumption of alcohol, starting when he was still a schoolboy. In drinking contests at Oxford, he was always the last man left standing. There are no records for him prior to 1750 but his story was reprinted many times from 1755 up until 1827. I doubt whether one whose fame depended on out-drinking ‘the stoutest freeholder in England’ lived to a great age. I might contact the alumni at Oxford Uni. for more information on one of their less salubrious graduates.

Another hat is thrown into the ring along with tombak and Thomas ‘ Buck’ Whaley.

The final reference to the toper, Tom Buck I could find is dated 1859: ‘Oxford During the Last Century’. If the snuff is named after a person then ‘Tory Tom’ is a suitable candidate. His story in ‘The British Essayists’ was repeated a great many times until 1827 and was therefore likely to be more familiar to English readers than other suggestions, perhaps. Apart from the timing, a point in favour is the fact that the name in print is always ‘Tom Buck’ – just like the snuff.

The name of a prolific boozer, womaniser, and familiar of every ‘London vice from Westminster’ sounds like a fitting choice for naming a snuff. After all, I doubt many snuffs are named after saints or holy people. As with other suggestions, however, there is only circumstantial evidence to support it.

I contacted the Oxford University Archives at the Bodleian Library for more information but there is a delay of ten working days.

Tombak is certainly a possible candidate for the origin of the name, but the sheer paucity of contemporary references weakens the candidacy, in my opinion.

Although Buck as a surname was common enough in the 18th century (as revealed by the Ancestry site) it was during that century that it was first used as a nickname for a reckless, spirited young man. It was around the time Whaley was elected MP for Newcastle, Co. Dublin in 1785 that his escapades become better known and that he acquired the nickname Buck. His story is told in some detail in ‘Libertines and Harlots’ by Norman Milne.

Then there is the other Buck, Tom Buck or ‘Tory Tom’ whose spirit was evident from the day he was put into breeches. I won’t know for certain until I hear back from the Oxford Archives, but suspect that ‘Tom Buck’ was but a nickname for someone who enrolled at the university under his real name, but to avoid scandalising his parentage (perhaps nobility) his true identity is not revealed.

My belief is that the snuff acquired its name from Thomas ‘Buck’ Whaley and Tom Buck or Tory Tom and any other Buck whose libertine lifestyle justified the moniker. In this sense ‘Tom Buck’ is not necessarily named after an individual but is a metaphor for one whose unusual lifestyle is exemplified by the likes of the people described. That for me is the likeliest explanation. . It also ties in with Tom Buck being a ‘racier’ version of Queens.

I have already had the opportunity to see the texts you presented and I also noticed a certain relationship between these people with the nickname “Buck”. I suspect it would be possible to dig up a few other similar cases, but I won’t do it myself. I resent British databases for having paid subscriptions to view text, so I can’t help in this matter. The minimal preview itself is quite puny for professional judgment.

However, I think it is quite beautiful that over the dozen or so years since the original debate, the view on the name of this snuff has changed quite a lot. We stopped looking for tombak or Thomas ‘Buck’ Whaley, but we started to notice a certain linguistic dimension to this name. And the most beautiful thing would be if both theories were correct. Which I can basically imagine and would explain the choice of the name “Tom” (being the first part of the word tombak). It would be a word game within a word game. We would have the word “tobacco” (somewhat consistent with the nomenclature of snuff) and the word “Buck” meaning someone strong. Combining these we would have Strong Tobacco/Strong Snuff.

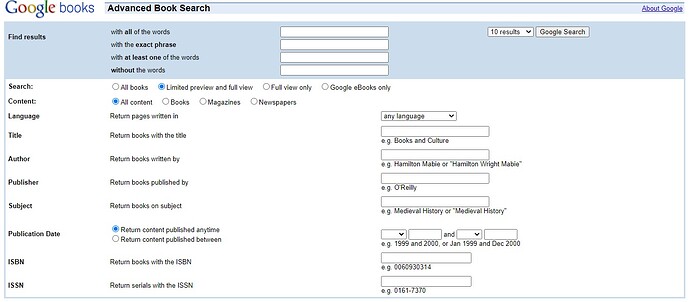

Thank you for your observations, Maciej. I’ll continue digging a little more but in the meantime would like to say that the Google Advanced Search is very useful, especially the Boolean parameters. Do you use this? I usually select full preview to skip the snippets.

I’ve noticed that digitalised documents seem to be stored on American servers as selecting Country: The UK usually results in 0 results.

Maybe you or someone else will know, but could it be that searching from Poland yields different results from that in the UK?

It was an American ex-pat. Leonard Fox, dead a long time now, and a snuff-taker since the 1930s who really kindled my interest in snuff history. I daresay any other poster, except you, would consider me to be a bit barmy going to all this trouble over a name, and that the general consensus would be – who cares

Yes, Google Books search results may vary depending on the country you are searching from. These differences may be due to several factors: location, copyright and content availability, language, local preferences and trends. Google tailors search results to the user’s location, which means that results may be more relevant to that country. For example, books available for sale in Poland may be more visible to users in Poland, while users in England may see results that are more relevant to that market. Books may have different copyrights and licenses in different countries. Some books may only be available in certain regions, which may affect search results. Results may be filtered based on the user’s preferred language. In Poland, users may see more results in Polish, while in England, results may be mostly in English. Google’s search algorithms may take into account local preferences and trends, which may lead to differences in search results in different countries. While the overall search results may be similar, these local factors may cause some differences in the books available and their visibility.

However, “google books” is just the tip of the iceberg, and the real gems are in other databases. “Web Archive” is also a good place. Have you tried “British Newspaper Archive”? Fantastic content, but unfortunately for a paid subscription.

As for the advanced search, the only thing that I find really useful in this function is searching by publication date. However, I prefer the classic use of special characters to narrow down the results.

I contacted the Oxford University Archives at the Bodleian Library for more information and received a reply today. As I suspected, there is no record of a Thomas (Tom) Buck being enrolled at one of the Oxford colleges during the first sixty years of the 18th century. Given his reputation it’s hardly surprising that he remains incognito.

Thank you for your enquiry. I’m afraid I cannot find any evidence that Thomas or Tom Buck attended Oxford University in the 18th century. I have searched Joseph Foster, Alumni Oxonienses 1715-1886 and the earlier volume Alumni Oxonienses 1500-1714. There are only two Thomas Bucks in these two volumes and, based on the dates, neither seem to be the right man:

Thomas Bucke, s. of Thomas of Newburye, Berks., pleb. Pembroke College, matric. 6 Nov 1629, aged 18; B.A. 27 Jan 1631-2

Thomas Bucke, s. of James of Marylebone, Middlesex, arm. Wadham College, matric. 17 Jun 1796, aged 19.

My conclusion is that ‘Tom Buck’ refers to a generic character, young (probably dying young), spirited, totally sybaritic and with enough inherited money to fund his rakish lifestyle.

I’m not a liberal. But something not being discussed is that in this era a Tom could have been a patron of prostitution and Buck was the term used for a breeding male slave, so muscular and black with a large penis. Let’s not rule out that Tom Buck could have been euphemism for a whores dream. I mean, even in recent British History using penile euphemisms for popular cultural products is still happening.

Unlikely I think, that pejorative doesn’t really occur in the UK as a racial term. A John would be more usual as a ‘user’ of prostitution in the UK.

I thought we were discussing syntax in an era which the North American aristocracy was still English. Our dialects had yet to to diverge. Slaves were registered livestock in both England and the colonies, “pejorative” would not be relevant syntax in context. That’s like saying bull, billy or stud are pejorative terms for current livestock. Jack (a sailor) and Tom (as in tomcat) are certainly dominate in early New England writing. Gropecunt Lane was no longer listed in municipal maps at of time, yet Codpiece Alley had replaced it. Granted, we could respectively identify ones dialect through writing now, but we would be speaking/writing the same dialect late 18th early 19th century.

My point? Never underestimate the lascivious innuendo of any Germanic language. But I could be full of shit too.

You are!

Slavery in the era to which you refer was never legalised in England, either by statute or Common Law. Moreover, the date Tom Buck was added to the Sharrow List was 1844 by which time the British slave trade had not only been abolished (1807) with naval squadrons enforcing it but the institution of slavery was outlawed in all British overseas territory in 1833. So much for slaves being registered livestock in England.